It’s an odd thing that real crime, stalking in our own vicinity, terrifies us, but in fiction, and at a distance, we love it. There’s an obvious reason for that. It’s fiction. It’s not true. It allows us to enjoy all the thrill, the suspense, the exploration of our darker sides, without any danger of being the next victim.

There’s another reason for its appeal. It allows us to pretend that justice will always prevail and that somehow the truth will be revealed. In real life, we know that’s not true. We know that criminals regularly get away with everything from parking on a double yellow line to murder. In fiction, we can attempt to redress the balance – if not to see that justice is done, at least to let the truth be told.

Crime has been a central feature of fiction for a long time. Daniel Defoe, in 1722, delighted in the exploits of MOLL FLANDERS, 12 years a whore, 12 years a thief and 8 years a transported felon, even if she is a reformed penitent at the end. Jacobean tragedies drip with gore and murder. Shakespeare’s Macbeth is nothing but a tale of a man tempted into murder and utterly corrupted by it. Chaucer’s Pardoner’s Tale is a lurid exploration of a triple self-defeating murder. If you choose to see the Bible as not one hundred percent literal, you could say that the story of Cain and Abel is the first fictional crime story.

In its fascination with crime, fiction was running neck and neck with true crime and its consequences, which have always been treated as a form of entertainment. A subgenre of contemporary crime fiction wallows in the gore and horror committed by psychopaths. A crime novel of that ilk, set in the Middle Ages, would probably concentrate on the punishment rather than the crime. Always in public, after confessions had been obtained by torture. Branding. Flogging. Humiliation in the stocks. Blinding. Ear cropping. All manner of amputations. Beheadings. Slow throttling on the end of a rope, boiling for poisoners, and the exquisite slow agony of hanging, drawing and quartering, or burning at the stake.

Who needed fiction when you could be titillated by real horror? As soon as printing was introduced, broadsheets appeared, describing executions. The Chaplain of Newgate issued regular accounts of the lives of all the criminals hanged at Tyburn. As soon as we had regular newspapers, sensational crime and punishment became standard reading. They created an appetite and fiction stepped in to feed it. The crimes of Jack the Ripper, reported in the press in ghastly detail, were already featuring in fiction before the last murder had been committed.

Early fiction could titillate, speculate and imitate, but what it couldn’t really deal with was detection of crime. Not until we had detectives to work with. THE MOONSTONE, by Wilkie Collins, published in 1868, is often held up as the first detective crime novel, featuring a policeman, Sergeant Cuff, although Dickens’ BLEAK HOUSE, published in 1852, had already featured the investigating Inspector Bucket and Edgar Allan Poe was writing detective novels set in France in the 1840s. After the early police detectives came the gentlemen detectives, most significantly Sherlock Holmes in 1887. The SHERLOCK HOLMES stories highlight two aspects of crime detection that had begun to change things utterly in the 19th century, making the Victorian world a half-way house between an almost fantasy past and our very real present day. Holmes’ world had a police force and it had the beginnings of forensic science.

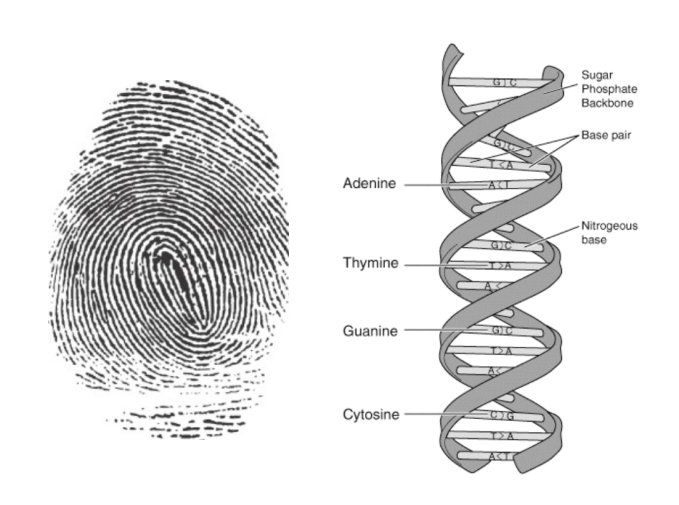

Contemporary crime fiction has such a treasure-trove of science to draw on that you sometimes wonder how the right answer doesn’t spring out on page one. Fingerprints. Luminol to detect blood. Analysis of poisons, of fibres, of insect development. Identification of bullets and guns. DNA. Computers to collate and connect evidence. CCTV tracking victims and villains.

Much of this was beginning to develop in the 19th century, although, perhaps, not as fast as it might have done. Mark Twain was using fingerprints for detection in LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI before the Police got round to doing so. From the 1880s, the Home Officer had official forensic scientists at work in laboratories, by which time Sherlock Holmes had already written his monograph identifying 243 different types of cigar ash – although I am not convinced it had been subjected to peer review. People began to believe in science as a source of irrefutable evidence. They believed so strongly that we had men like Sir Bernard Spilsbury, pathologist, in the early 20th century, who was so adamant in his declaration of scientific facts in court that no one dared to question him. He was the pathologist who identified marks on a piece of skin dug up in a cellar as indisputably belonging to the wife of Dr Crippen. Interesting that in recent years, DNA analysis of the same skin has suggested it might have come from a man. Which opens up all sorts of possibilities in the Dr Crippen case.

Since the mid 19th century, as well as forensic science, we’ve had a professional, legally empowered police force, in every county, taking responsibility for the prevention and detection of all crime everywhere. This was seen as a dangerous innovation in some eyes. The French had had police in some form for a long time, and look at them. We didn’t want that sort of officious encroachment on the liberties of the freedom-loving Englishman (Briton). When the first police officer was killed in the line of duty, it was ruled as justifiable homicide.

But we did have law enforcement before the police. First, of course, there must be law to be enforced. Some laws are purely repressive, imposed from above on an unwilling populace, but many, especially the ones that last, grow out of custom, for the common benefit of all. No one wants to live in a society where your neighbour is free to kill you or help himself to your possessions. One of the principal (theoretical) functions of a king was to make and codify just law. Many Saxon kings were noted and honoured for it. William I is just William the Conqueror, but Alfred of Wessex was Alfred the Great. In Wales, Hywel Dda is remembered as the great law giver and codifier. The criminal and inheritance laws of the Cyfraith Hywel were abolished after the conquest of Wales in 1282, but his civil laws remained until the reign of Henry VIII.

How was the law enforced, before we had police? see part II

“Interesting that in recent years, DNA analysis of the same skin has suggested it might have come from a man.” I didn’t know that, Thorne

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’d emphasise “suggested.” It has also been suggested that a “scar” that Spilsbury identified (matching Crippen’s wife) was actually just a fold in the skin.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You do find some brilliant ‘suggestions’!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was really surprised by The Moonstone – it had so many ‘modern’ features. The fact that Mark Twain was using fingerprinting before the police did is even more surprising! The GCSE history Syllabus this year has a paper on Crime and Punishment from 1500 to the present day and one of the main questions (yesterday) was on the development of policing. Fascinating stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll confess: I knew about Mark Twain and fingerprints, thanks to an episode of Alias Smith and Jones.

LikeLike

😀

LikeLike