Kings made laws and they wanted to see them enforced by more than wishful thinking. Someone had to do it. In England, the Normans preserved the Saxon role of Shire Reeve, or Sheriff, an appointed protector of the King’s interests in every county, with soldiers at his command. They could be hard-hearted extortionists, like Robin Hood’s Sheriff of Nottingham, but Ellis Peters, in her Cadfael novels, chose to present them as officers of the law, because, if you’re going to write historical crime novels, you have to have someone representing the authority of the law. Whether Sheriffs really were effective law officers in an age of anarchy and civil war, I doubt, but of course the focus of her books is Cadfael, a herbalist, which makes him an early forensic scientist. He is also, most significantly a monk, guided by religion.

It’s impossible to look at crime in the past through purely secular eyes. The Catholic church, its authority and its teachings, influenced every action and every thought in the Middle Ages. Crime and sin were impossible to separate. Social stability and cohesion required an absolute regulation of beliefs, without which there would be anarchy, starvation, the end of the world. Life was so precarious that the men who controlled your entry to the next life had more influence than those who controlled this. And the church knew it. Cadfael the monk may have been happy to work hand in glove with the King’s sheriff, but when Henry II tried to exert jurisdiction over the church, he lost, thanks to the martyrdom of his bloody-minded archbishop, Thomas a Becket. From then on, the church dealt with its own affairs including any crimes and misdemeanours committed by its own clerics (a legacy that has haunted us to this day). It resulted in a fabulous get out of jail free card called Benefit of Clergy. In an illiterate age, churchmen were the only ones who could read and write. If you could prove in court that you could read, you could claim to be a cleric, and get away with a sentence of penitence and 3 hail Marys. If not, you’d face the gory horrors of civil punishment..

Punishment came after a trial and our present court system derives from Henry II’s attempts to bring all his subjects, high and low, under royal control and a common law. Crime was at first dealt with by the courts as a private matter just like land rights or other civil matters. Citizens who wished to accuse another of a crime could purchase writs, which would summon the accused to court to face trial. These writs were very precisely designed for different events, and there were a lot of them, so it was essential to purchase the correct writ. A complicated business in which mistakes could easily be made, so a body of men quickly grew up, qualified to advise you, for a sizeable fee, which writ to apply for. Some of them could be paid to present your case in court. They were called lawyers.

Lawyers were not really detectives, but in a world where there was no professional detective agency, you could use a lawyer as your detective in crime fiction as C J Sansom does in the Shardlake stories set in Tudor times. Shardlake is commissioned by various important people at court to investigate mysteries that concern them.

Who else besides Queens and ministers could commission enquiries lower down the social scale? Magistrates were a possibility. Local men were appointed to maintain the peace in the reign of Richard I, and after the Black Death in the mid 14th century, with the consequent breakup of social cohesion, Justices of the Peace were established in every county with the power to restrain rioters and other criminals, bring them to account and punish them. They quickly replaced sheriffs in matters of law and order, and James I referred to them as his eyes and ears in the counties. Because they were unpaid, it goes without saying that they were drawn from the idle rich, not from the overworked poor, so they naturally defended the interests of the landed gentry. Until the mid 18th century, they could sentence culprits to death, floggings and transportation, without having to wait for a judge to visit.

Magistrates were aided by parish or night watchmen, appointed in rotation, to keep order and apprehend villains. Constables were ordinary men, not necessarily the smartest, like Shakespeare’s Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, and they were obliged to serve for a year, while continuing with their normal work. As the duty was an unattractive one, many men paid substitutes to take their place. In the end, in London, it was happening so often that the duty to serve was replaced by a tax to pay for permanent constables.

If you fancy crime fiction featuring investigating magistrates aided by their parish constables, try DEATH COMES TO PEMBERLEY, by PD James. Or if you want to wallow in every aspect of 18th century crime and its consequences, the POLDARK novels of Winston Graham have it all – riot, wrecking, poaching, murder, magistrates, judges, lawyers, trials, imprisonment and hangings.

One potential focus for crime fiction, which has been involved in genuine detection for centuries is the role of Coroner. Coroners have been around since 1194, their job being to look after the financial interests of the crown, which is why they still, today, deal with questions of treasure-trove, deciding whether hoards of gold unearthed by metal detectors should belong to the crown. It is also why they have, from the start, been concerned with investigating sudden and unexpected deaths. Nothing to do with justice. Everything to do with money.

When the Normans conquered England, they discovered, surprisingly, that their conquered Saxon subjects were given to killing any stray Norman found wandering alone. They introduced a fine, called Murdrum, from which we get the word Murder, imposed on any parish where a dead body was found, on the assumption that it was Norman, unless the parish could prove it was Saxon. So coroners investigated such deaths, to see if there was a fine to be collected. They investigated deaths in case there was a suggestion of suicide, because a suicide’s property could be confiscated. In time, money matters set aside, they simple investigated any unexplained or violent death reported to them, by holding inquests, not in court houses, but more likely in local pubs, viewing the body, considering evidence and coming to a conclusion with the aid of a local jury.

Unexplained deaths were not always murders, and murders did not always produce signs of violence. In a world where death by every conceivable disease and accident was common, and medical knowledge was limited, how many murders went undetected? Even today it can happen. Harold Shipman was convicted of 15 murders, but it’s thought he might have killed over 200.

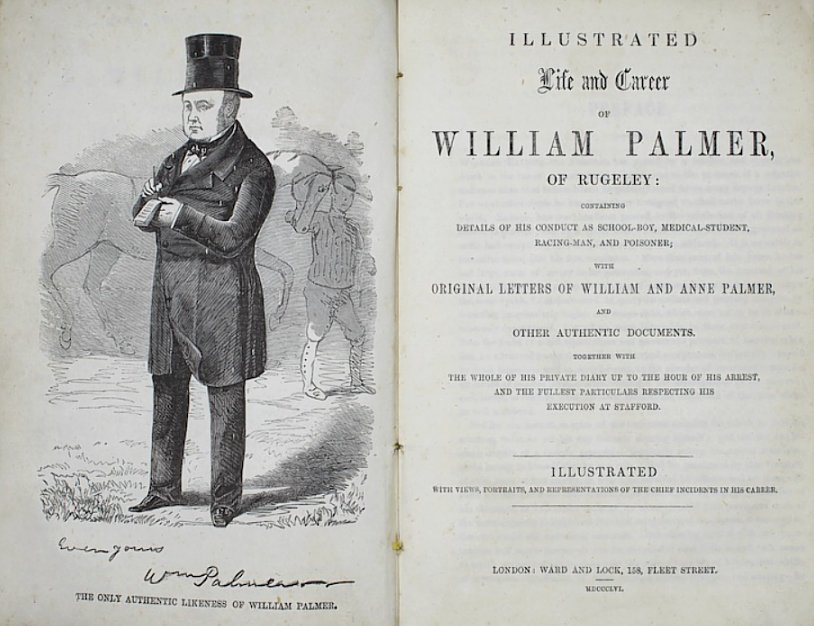

There could be autopsies. The autopsy performed on a victim of William Palmer the poisoner in 1855 was carried out in public, by a medical student and an assistant chemist who was so nervous he had to be given brandy by Palmer. Palmer was present, jogged elbows, causing stomach contents to spill and mislaying jars with organs in. Samples were sent to an expert in London, who was so disgusted he demanded a second post-mortem, in a letter that Palmer intercepted.

Palmer’s case is another crime that has often featured in fiction.

Whatever officials were appointed to deal with crime, it was, ultimately down to the ordinary citizen. They weren’t just expected to serve their term as constables. Everyone, without exception, was obliged to raise the Hue and Cry, to shout Murder! or Stop Thief! if they witnessed a crime. Everyone was obliged to join in the pursuit for as long as it took, and to hand the culprit into custody. How eager you were to fulfill this duty probably depended on whether you had something better to do. In order to encourage citizens to do their duty, the state began to offer rewards from the late 17th century. As a result, a body of virtually professional Thief-takers grew up, making a living out of collecting rewards. A perfect recipe for organised crime. Thief-takers became the biggest criminals of all, blackmailing real thieves, using extortion against law-abiding citizens and staging fake crimes in order to claim rewards. One of the most notorious was Jonathan Wild, the virtual Godfather of London, until he was eventually hanged for receiving stolen goods in 1725.

There were novelists at work, such as Henry Fielding, author of Tom Jones. It’s surprising that he never chose to write a crime detection novel. Surprising because, besides being a satirist, he was also a magistrate, living in Bow Street and he was responsible for setting up the first effective crime reporting system, urging citizens to report crimes to a permanently functioning magistrates court, which would then send out a properly salaried force of Thief Takers to detect and pursue the criminals. These thief takers called themselves Principal Officers but everyone else called them Bow Street Runners.

And then we were nearly there.

For what came next, see Part III

punishment, science and law in Part I

So much here I didn’t know. I’d never linked the word coroner with the crown, nor knew about Mordrum, William Palmer (though I intend to find out more about him), or Fielding’s role as a magistrate and what it led to. I can recommend Ariana Franklin’s Mistress of the Art of Death. The title character was educated in Sicily (if I remember correctly) and was fascinated by what the body could tell you about a person’s demise. The books are set in Henry II’s time and, as she’s a mere woman, she’s dependent on her male companion to appear to be the one in charge. I’ve also read most of the Shardlake mysteries – two left, but the last is over 800 pages long and will require significant time and energy. PD James is a writer I love, but I’d always thought Poldark would be a sensational bodice ripper sort of genre. I’ll add the first book to my list.

LikeLike

I will not lie. There are a few bodices ripped in the Poldark books. But much else too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds fine by me!

LikeLike