This is what happens with a murder. The wicked deed is done, the body is found, police are called, they investigate, catch the murderer, he (or she) is charged, sent to trial, convicted and sentenced. End of story. We all move on. That is the basis at least for most standard police procedural crime fiction. Finding the body, following clues and catching the killer is what it’s all about.

Not so, always, in real life, or death. Sometimes, finding the body is the awkward bit that’s missing. If there’s no murdered corpse, can we be sure there was a murder, and a murderer? If someone simply vanishes, is that enough?

It was generally thought that it wasn’t enough, after a notorious case in 1660, which became known as the Campden Wonder. William Harrison set out from Chipping Campden and vanished. His son Edward and his servant John Perry went looking for him and found nothing but slashed and bloodied clothing. No body. Perry was questioned. Or maybe “questioned” was too mild a term, because he admitted that William Harrison had been murdered by Perry’s brother Richard and mother Joan, in order to rob him, and had dumped the body in a pond. The pond was dredged. Nothing. All three were charged with theft and were persuaded to plead guilty to avoid a serious sentence. Bad move, because they were then all three, as convicted felons, charged with murder, found guilty despite their protestations of innocence, and hanged.

Two years later, the murdered man turned up alive and well. His story was that he’d been abducted, sold into slavery in Turkey and had finally escaped and come home. Hmm. Whatever the truth, he was very much alive and his convicted murderers were very much dead.

As a result of the Campden Wonder, it was generally accepted that there had to be a body before anyone would be convicted of murder. Or if not an actual body, at least a bit of one.

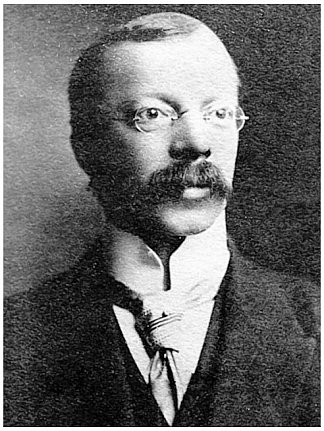

When Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen’s wife Cora went missing, he claimed she had left him and gone to America with a lover. His story might have been believed, if he hadn’t made the mistake of making a run for it, with his mistress. His property was searched and part of a human torso was found buried in the basement. Heroic champion pathologist, Bernard Spilsbury identified it as Cora’s remains, on the basis of a scar which would match one she had. No one ever presumed to question Spilsbury, so Crippen was convicted of Cora’s murder and hanged in 1910. Shifting forward nearly a hundred years to 2007, DNA tests were carried out on the preserved tissue and concluded the body had been male and the so-called scar contained hair follicles which meant that it couldn’t be a scar. Therefore, it was not Cora. It does still beg the question of who had really been stuffed full of scopolamine, dismembered and buried in the doctor’s cellar.

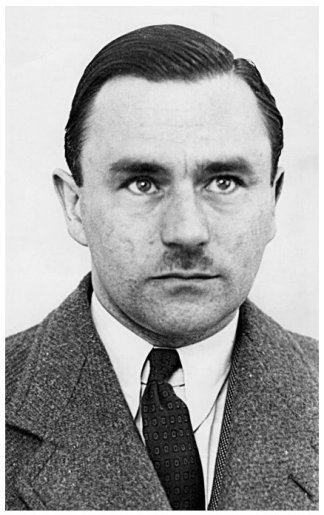

In the last years of World War II, convicted fraudster John George Haigh decided that his mistake in previous crimes had been to leave his victims alive to testify. Much better to kill them before they could do so. Bodies would result in murder investigations, so his obvious course was to eradicate them entirely in vats of sulphuric acid. He worked on the assumption, commonly held, that there could be no charge of murder without a body to substantiate it, misinterpreting the legal phrase “corpus delicti” (body of the crime). It does not mean that there has to be a body as evidence, but there has to be a body of evidence. In Haigh’s case the body of evidence included a set of dentures that hadn’t fully dissolved. It was enough to convict him and he was hanged in 1949.

So there has to be a body of evidence to support the claim that a murder has taken place. Much of it might be forensic – blood, for example, or, these days, DNA. It might also be lack of evidence – no visual or digital sign of the victim still being alive, no credit cards used, no CCTV footage beyond a certain point, no phone calls made, no usual activities pursued.

It might be evidence of behaviour by the victim or the suspected murderer before the crime – financial clues, hints of fear, neighbour’s suspicions, worrying emails. All this is used in my novel BETHULIA to convict a man of murder, even though there’s no body to prove it. It doesn’t mean no doubt remains, of course.

Behaviour by the suspected murderer includes cyber behaviour, these days. That is certainly a tricky one for crime writers. Murderers trying to be clever so often turn out to be as thick as the proverbial, if not thicker. They have a remarkable tendency to research options for murder and disposal on-line. Bad for crime writers, because if any of us were subject to raids by the police, with our laptops confiscated and our Google searches forensically examined, we’ll all be in gaol.

Powerful stuff! Bethulia was so neatly done, I read it again straight afterwards. Looking forward now to Cold in the Earth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I do hope you enjoy Cold in the Earth in its turn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can be sure of it!

LikeLike