I thought I’d write, now and again, about books that made a serious impact on me and influenced me in some way. Because why not?

Starting with a children’s book. The Silver Sword by Ian Serraillier.

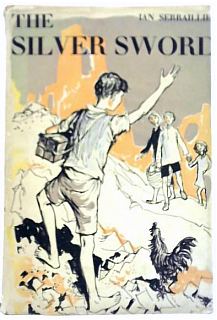

The link is to the current version available on Amazon, but the illustration is of the edition I knew as a child. Because, for me at least, the illustrations were always a vital part of my childhood reading. I read and reread all the Narnia novels, though I never really cared for the stories and their heavy-handed theology. Their chief appeal lay in the fabulous illustrations by Pauline Baynes.

The Silver Sword, which was first published in 1956 and as a paperback in 1960, is set in World War II. If you don’t know it, the plot is thus:

School teacher, Joseph Balicki was imprisoned by the Nazis but escapes and makes his way back to his family home in Warsaw, only to find it and most of the city in bombed-out ruins, and his wife and three children missing. He discovers a paperknife, the silver sword of the title, in the rubble of his house, and gives it to a child scavenger, Jan. He asks Jan, if he ever comes across Joseph’s wife and children, to tell them that he’s going to try and make his way to Switzerland.

In his absence, his wife Margrit has been sent off to a labour camp in Germany, and the three children, Ruth (13), Edek (11) and Bronia (3) have been surviving in the ruins. Ruth has stepped into the role of mother, starting a school for abandoned children, and Edek has been stealing food and clothing for them until he’s captured and taken away by the Germans. In 1944, the city is finally occupied by the Russians, and Jan joins the children Ruth is caring for. When they recognise the paperknife among his treasures and hear his story, they decide to head for Switzerland to find their father.

First stop is Posen, where they have learned that Edek had escaped from a labour camp. He is found, suffering from TB. They reach Berlin, occupied by the allied forces, and head south, facing many difficulties including those posed by authorities trying to resolve the refugee situation. They make it to Switzerland in the end, of course, and are reunited with their parents.

Why did The Silver Sword make such an impact on me? It’s a story of the Second World War, and when I was first reading it, I was immersed in war stories. I was still grasping the idea that WWII was not just fantasy history, but very recent history that my parents had lived through. It had ended less that ten years before my birth and television offered an endless diet of weekend films about the exciting dramas and extraordinary heroics of the war, with a triffic amount of jolly good chaps and stiff upper lips – fighter pilots with tin legs, bouncing bombs, cruel seas. The films were mostly in black and white, which was appropriate because there was still a very black and white attitude to the war. Good v Evil. No grey areas, no nuances, none of the iconoclasm that came later.

The Silver Sword was my introduction to the idea that nothing about war was simple, except for one eternal truth: regardless of whichever side is right or wrong in a war, it is complete shit for the civilians whose lives are ripped apart by it, and when the fighting stops, and peace treaties are signed, it is still complete shit for the civilians, whose lives are still smouldering wrecks. Whoever wins or loses, children are always the victims of war.

The moral ambiguities offered by The Silver Sword sweep away the notion that there can be nothing but evil monsters on one side and virtuous heroes on the other. The children come up against friendly helpful Russians, Brits and Americans, but also Germans, including a Bavarian couple proud of their sons who fought for Hitler. But they also come across heartlessness and, worst of all, bureaucracy. Imagine a world where the homeless and dispossessed as seen not as people but as a problem, and where the main aim of authorities is to round up refugees and send them back to the hell they fled from. In war, and its aftermath, does the notion of law and order make sense? Jan is a thief, but what made him so and why should he be otherwise? When he is caught looting American trucks and put on trial, why should he see his actions as any different to what the American forces are doing to the Germans? Why should any of them return to Poland just because the prevailing authorities want them sorted out like pieces on a games board?

The Silver Sword is an adventure story, with enough thrills to satisfy any child reader, but it is no Famous Four Go Mad in Poland. I like psychological depth in my books, and this has plenty. Jan, in particular, is a complicated character, a damaged orphan without morals or scruples, who has lost the ability to relate to anyone or trust any human, but who forms attachments to animals instead. Is he reformed and turned into a saint by kindly patience and moral instruction? No way. Ruth, as the eldest, becomes the eternal mothering figure, competent, determined, nurturing, taking care of everyone and everything, but then, when she has finally brought them all to safety and reunited them with their parents, she is the one who can’t cope. The strain of years of responsibility forced on her too young final catches up with her. This unexpected but perfectly understandable conclusion quite shocked me as a child.

You know that she, like the others, will come good, healed of her injuries and traumas, because it is, after all, a children’s story and there has to be a happy ending. But it was an eye-opening introduction for me to the un-heroic cruelties of war, and it is still painfully relevant today.

I did post about my one and only personal experience of World War II:

How Travel Broadens the Mind.

This book was in the stock cupboard in my first school as a teacher. I hadn’t read it and, sad to say, I judged it by its dull cover (not the one you show here). There were other really old-fashioned books in there that were unrelatable and dreary. I realise now that I have missed something important and intend to rectify it.

LikeLike

Aha! Never judge a book by a redesigned cover. I certainly wouldn’t call The Silver Sword old-fashioned, let alone dreary.

LikeLike

That’s recommendation enough for me!

LikeLike