Let’s talk about another book that was an early inspiration to me. Swallows and Amazons, by Arthur Ransome. Or rather, a series of books, because I was an ardent reader of the whole lot, although I generally preferred the Lake District ones.

The series begins in 1929, with four children, the Walkers, John, Susan, Titty and Roger, aged at the start from 7 to vaguely 12 or 13, and brought up on tales of adventure and derring-do. They embark on a sailing and camping adventure with their dinghy, the Swallow, (complete with flag made by Titty from a pair of knickers) and find themselves both competing and combining with a couple of pirates, Nancy and Peggy Blackett, with their dinghy, the Amazon.

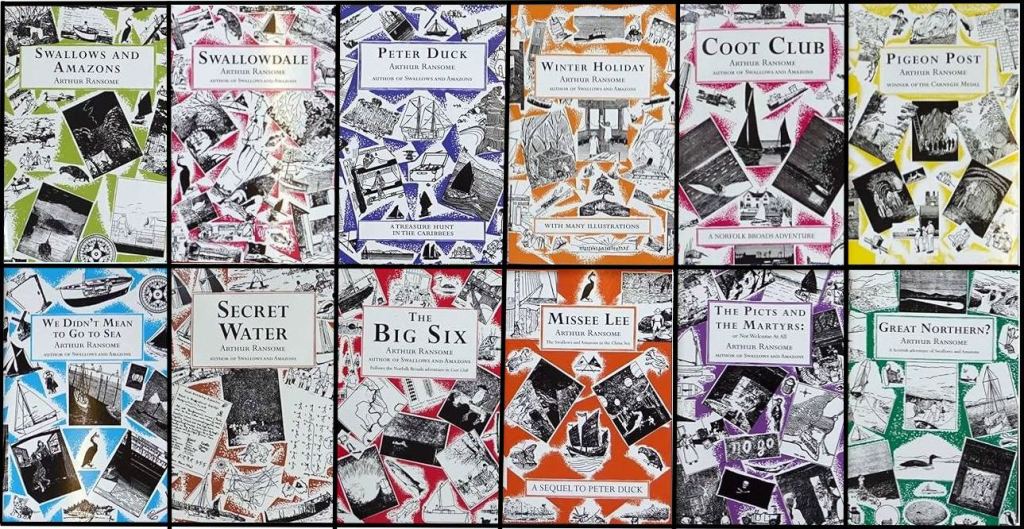

In later volumes, Swallowdale, Winter Holiday, Pigeon Post, The Picts and the Martyrs, and the rest, Coot Club, Peter Duck, Secret Water, etc, other characters are introduced, and the action moves to East Anglia, the North Sea and distant lands and seas, if only in imagination. Two of the books, Peter Duck and Missee Lee, are – can you have fictional fiction? They are wild adventure stories invented by the children themselves. In one, We Didn’t Mean To Go To Sea, spiffing childhood adventure turns in genuine drama.

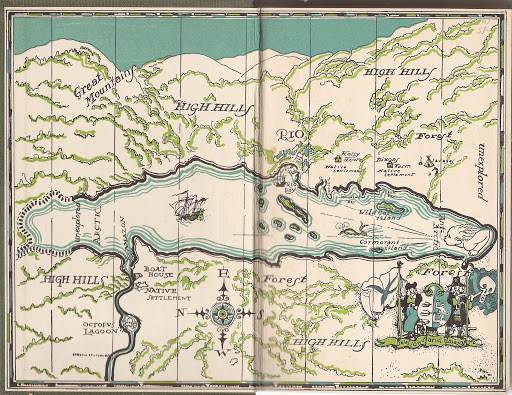

Best thing about them all, to me, at the age of 10 or 12? They had maps. How could I possibly resist books with maps?

The series had a profound influence on me. Primarily a very active influence. It resulted in me and my best friend digging up a large patch of turf from our back lawn, making a camp fire and cooking corned-beef hash on it. Or more accurately, corned-beef ash. I still feel the dish only works at its best if it is flavoured with smoke and little flakes of charred wood.

We bought, or more probably persuaded our parents to chip in to buy us, a tent, in which we camped by our camp fire. When I say tent, I mean the real thing. This was definitely not the age of glamping. Tents, in those days, were made of good solid canvas, with wooden poles and pegs. No groundsheet attached; we used her father’s hammock, kept from his war-time navy service. Absolutely nothing as decadent and effete as a fly sheet. One single layer of canvas, which on no account could you touch while inside, or you’d bring the rain water pouring through.

There were no lakes or suitable rivers in our area, so the sailing part of our two-girl re-enactment society had to remain imaginary. The paddle boats on the boating lake in Wardown Park were not an adequate substitute, although there was an island that we itched to land on and claim.

What other inspiration did the books offer, when I was a child? They certainly kept me reading, every night when I went to bed and every morning when I woke to the sound of Handel’s Water Music from my parent’s radio (Bakelite Wireless with smoky glass bulbs and a perpetual whine). They offered escape, because while they featured straightforward children without magic or super-powers, they were children of a different class and a very different era (boarding schools and Empire), so they were just sufficiently alien to keep me entranced. I also gained a basic knowledge of semaphore, charcoal-making and patterans. Always useful.

One thing I certainly found in the books was character study. Is it why I’ve always preferred books about characters rather than plot? The children at the centre of the these books are all believably drawn, unique individuals – John the Terribly Responsible, desperate to live up to his naval commander father’s approval, Susan the eternally busy housewife, forever making campfires, Titty the intensely imaginative one, Roger the future engineer, Peggy the obedient follower, Nancy the enthusiastic and irresponsible tomboy.

It’s really Nancy who connects my understanding of those books as a child, and my reassessment of them many years later when I came to read them to my niece. Approaching them anew as an adult opened my eyes to so much that simply passed over my head as a child. The books are about the children, but we also get to glimpse the adults involved in the background, and their carefully concealed reactions to what were actually, in adult eyes, quite terrifying situations.

In Swallowdale, when the Swallow hits a rock and sinks, John, theoretically responsible for his younger siblings, rushes to tell his mother that something terrible has happened. To John, the sinking of his ship is surely the worst thing in the world. Fortunately, he’s accompanied by the Amazon’s Uncle Jim who butts in with a hasty assurance that Mrs Walker’s children are all perfectly well and unharmed. The need for Uncle Jim’s reassurance totally missed me as a child. As an adult, I understood it perfectly.

Likewise, the carefully constrained reactions (probably concealing near heart attacks) of the Walkers’ mother in Suffolk and father in the Netherlands when, in We Didn’t Mean To Go To Sea, the children accidently find themselves sailing across the North Sea in fog and an horrendous storm (possibly the best book of the whole series).

Meanwhile, Nancy Blackett… Real name, Ruth, but she’s a pirate, and so she has to be ruthless. While she’s about the same age as John Walker, she’s his polar opposite in character, irresponsible, brazenly naughty, and reckless. She’s not seeking anyone’s approbation. She punishes her uncle for being boring and she wages war on her prim and proper great aunt. Or does she? Reading the books as an adult, I began to pick up hints that made Nancy a far complicated character and, being a novelist myself by then, I began to look at all the characters anew, in order to predict their future lives.

If John were 12 or 13 in the first book that is set in 1929, and almost certainly bound for naval college rather than Oxford or Cambridge, he’d be a young officer by the start of the war, maybe captain of some small corvette by the end, probably torpedoed and he’d insist on going down with his ship. Susan would end up in a secure hospital as a convicted pyromaniac. Titty would embark on a solo expedition up the Amazon, presumed lost, but turning up decades later having lived with uncontacted tribespeople who are now competent in Semaphore. Roger would naturally become an engineer, and work with NASA. Peggy would find a job being supportive of her boss, until she married to be supportive of her husband, having several children to whom she was very supportive, before finally, in her sixties, walking out on the lot of them and deciding to do her own thing.

But Nancy stumps me. I wonder more about her past than her future. If she were about the same age as John or maybe slightly older, she would have been born in the last years of World War I. Peggy would have followed a couple of years later, maybe 1918 or 19, in the midst of the Spanish Flu.

We glean a bit about the Walkers. Their father is a naval commander, their mother is from Australia, with tales of the Outback. The Blacketts are more nebulous. Father, Bob Blackett, is no more. He’d married Mother, Molly Turner, begat two daughters and died. How? Flu? War wounds? The last battle of World War I? What did he do for a living? The Blacketts were prosperous compared to the Walkers. They lived in a big house by the lake and kept a gracious launch. They had servants – cook, at least, and from the way Nancy was able to bully local policemen and impose her will on reluctant local farmers, it might be assumed that the Blacketts were the local land owners, squires, and the local farmers were their tenants. Nice work if you can get it, theoretically. Maybe not so nice if you’re Molly Turner, unprepared to be left alone to deal with the responsibility of two infants and a large chunk of Cumbria.

Mrs Blackett is portrayed as a bit dippy, rather less hands-on than Mrs Walker, quite bemused by her children, and maybe not altogether in control. On one occasion, Nancy has to grab the steering wheel to stop her mother crashing the car. On another, Mrs Blackett has been taken off by her brother Jim, to recover. To dry out, maybe? It suggests the possibility that Nancy, as the oldest child, might have been forced into taking on adult responsibilities to protect her alcoholic mother, and her tomboy irresponsibility was merely a liberating reaction to what she had to be at home. She claimed to be infuriated and resentful of the great aunt who arrived to make them wear dresses and recite poetry, but she later proved to be more concerned for her great aunt than she’d let on. What would become of her? Descent into schizophrenia? Special Operations Executive in occupied France? Society hostess? Headmistress? Sheep-farming recluse? Children’s author? The possibilities are endless and intriguing.

One thing that does occur to me whenever I think of the books: parents today wouldn’t rely on the maxim “Better drowned than duffers if not duffers won’t drown.” Their maxim today would be “Better not go anywhere near the water, just in case. And don’t ruin the lawn.”

This made my day. So fun!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Barb. If Swallows and Amazon and all it leads to isn’t fun, nothing is. Have you thought of sailing a small dinghy instead of relying on the ferry?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m more of a passenger than a sailor, so the dinghy option doesn’t appeal. ⛵️

LikeLiked by 1 person

A series that missed me by. I regret that a little now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was the appeal of having a series to plough through. I hated it when books ended. Not so bad when there was another to move on to.

LikeLike