We had thief catchers, and Bow Street Runners. Then, finally, in 1829, Bobbies, or Peelers, came along, when Sir Robert Peel established the Metropolitan Police Service with Commissioners, Superintendents, Inspectors, Sergeants and 895 Constables. If you are writing crime fiction, even for TV, it’s important to get the ranks right. How did Christopher Foyle manage to be Chief Superintendent at Hastings at least a decade before the rank was introduced?

The Met police, keeping the streets of London safe for nice people, proved such a success that in the 1840s official police forces were established in every county. But why did nosey and intrusive police forces suddenly become acceptable? It wasn’t because poor little widows needed to be protected from thieves or because honest working men needed to be protected from muggers.

In Jane Austen’s NORTHANGER ABBEY Catherine Morland, who has read far too many lurid Gothic novels, suspects that General Tilney has murdered his wife. The General’s son, Henry, mocks the very suggestion. “Miss Morland. Remember, we are English. Does our education prepare us for such atrocities? Do our laws connive at them?’ In other words, one cannot conceive of English gentlemen involved in such dastardly deeds. But earlier in the same book, when Catherine speaks of something horrible coming soon in London, by which she means a new novel, Tilney’s sister imagines ‘A mob of three thousand men assembling in St George’s Fields, the Bank attacked, the Tower threatened and the streets of London flowing with blood, a detachment of the 12th Light Dragoons called up to quell the insurgents.’ You could be confident of gentlemen behaving properly but there’s no knowing what the mob at the bottom of the social pile might do. 18th century law was obsessed with keeping them in their place, down there at the bottom, leaving gentlemen to enjoy their civilised lives and property without fear.

It resulted in what became known as the bloody code, which, by 1800, had made 220 offences punishable by death. Serious offences like murder, rape and arson, but also any potential attacks on a gentleman’s nerves or property. Poaching, of course. Theft of goods worth more than 1 shilling. Consorting with gipsies. Horse-stealing. Sacrilege. Being out at night with a blackened face. Evidence of malice in a 7 year old.

Miss Tilney’s imaginary riot required troops to charge the mob, and 1819, cavalry did charge a crowd of protestors at St Peter’s Field in Manchester. It became known as the Peterloo massacre. Across the channel, bloody revolution had ripped France apart. The ruling classes had been sent to the guillotine. Here, Chartism was on the rise. How long before revolution happened here? The industrial and agricultural revolutions were bringing masses of the great unwashed streaming into the dark and sinister cities. They weren’t gentlemen. They weren’t peasants who knew their place. They were lawless, Godless, ignorant, a potential threat to every decent person. So a police force was created to keep gentlemen safe from the vicious criminal underclasses who were lurking round every corner.

Fiction played its part in boosting terror of this supposedly lawless mass. Dickens did wonders with OLIVER TWIST, convincing every well-bred reader that there were Fagins and Bill Sykes and Artful Dodgers down every dark alley – although the same well-bred people were delighted to be entertained and thrillingly appalled by his public readings of Nancy’s murder. In Magwitch, in GREAT EXPECTATIONS, he portrays a convict as virtually sub-human. It was taken as obvious fact that the poorest were wretched and vicious because they were naturally criminal (rather than being criminal and wretched because they were poor).

The police, created to keep these nasty lower orders in check, were drawn from the self-same lower orders, because who else could go among them? And being of the lower orders, they were naturally assumed to be ignorant and stupid. Even in the last decades of the 19th century, this notion was central to crime fiction. Sherlock Holmes is an educated, intelligent gentleman, using his superior forensic powers to highlight the plodding stupidity of the police.

Class was such a huge issue in the 19th century that it limited what the police could do, even if they were legally entitled to do it. The uniformed police at Scotland Yard were tasked with patrolling, deterring, chasing and arresting baddies, but they were soon supplemented by a group of plain-clothed officers appointed to investigate and detect. Though still lower class, their native intelligence quickly detectives a reputation for doggedly getting to the bottom of mysteries. In 1860, the infant son of a gentleman, Samuel Kent, was brutally murdered. A detective from Scotland Yard, Inspector Jack Whicher, was brought in to investigate. A nursemaid was taken away, locked up and questioned, and that was fine: A servant. The police were there to deal with the criminal lower orders, but when Jack Whicher began to suspect Constance Kent, the baby’s sister, he was overstepping the mark. Common policemen had no business questioning and locking up nice, well-bred young ladies. He was dismissed and she was released. Five years later, she then admitted to the crime and served 20 years in prison.

It was a case that almost immediately inspired fiction, beginning with THE MOOSTONE. No murder, but a precious gem goes missing. The local bumbling police fail to get to the bottom of it, so a detective from Scotland Yard is hired. Sergeant Cuff (probably based on Inspector Whicher) is so wise and deep, that he prefers a rose to a diamond, but his vulgar presence in a genteel home is grudgingly tolerated and when he draws too near to the bone by suspected the young lady of the house, he is paid off and dismissed. He may be from Scotland Yard, but he is treated as a private investigator, working for a fee, and cannot possibly demand co-operation from anyone within a gentleman’s household. Ultimately, it’s left to the gentleman amateur, Franklin Blake, to get to the bottom of the mystery from his more entitled position..

The Constance Kent case has continued to inspire writers on fiction and non-fiction, long after Wilkie Collins, mostly recently, of course, with THE SUSPICIONS OF MR WHICHER by Kate Summerscale.

The nineteenth century gave us forensic science and a police force, but it also gave us a third important contribution to our subject. Bureaucracy. In the early 19th century, there was panic over the mis-recording of deaths by cholera, and in 1837, the registration of births marriages and deaths was introduced, requiring the cause of death to be certified by a doctor. It meant that everyone would now exist on paper.

There had been records before. In the 1530s, parish registers had been introduced, recording baptisms, marriages and burials, mainly to establish which parish had responsibility for which people. But it was possibly not to be baptised or married or, if you simply vanished, not to be buried. Before Tudor times, the vast majority of people lived and died without any record of their existence. But 19th century registration, along with the censuses held every 10 years, began the trend of officially recording every aspect of every individual’s life… In theory.

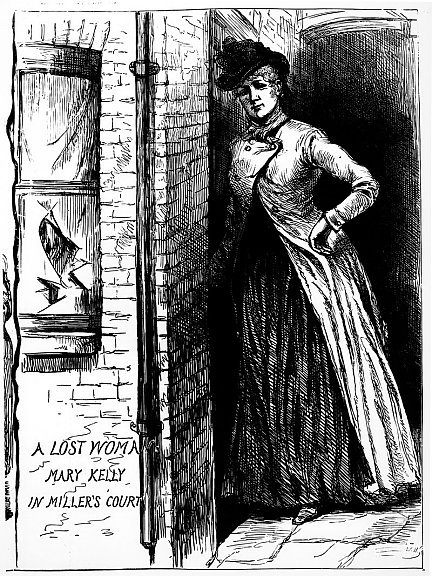

Take the case of a Victorian girl whom we should be able to track from cradle to grave. Mary Jane. Born in Limerick in 1863. When she was young, her family moved to Wales, possibly Carmarthen. Her father, John Kelly, worked in the iron works. She had a lot of brothers, one of served in the 2nd battalion Scots Guards. At the age of 16 she married a collier named Davies. She had a child but her husband was killed in an explosion two or three years later and she moved to Cardiff to live with a cousin. She worked as a prostitute there but spent a lot of time in an infirmary. In 1884, she moved to London where, opinions divide, she was either placed in domestic service by nuns, or went to work in a high-class brothel. She accompanied a gentleman to Paris and came back calling herself Marie Jeanette. She moved in with Joseph Barnett and lived at Miller’s Court, Whitechapel. We know all this in huge detail, because it was broadcast around the world when, on the 9th November, 1888, she became the last recorded victim of Jack the Ripper. We know everything about her from evidence given after her death, and yet the only official document recording her existence is her death certificate. There is no actual record of her birth, her marriage, her baby, no police records, no infirmary records, no convent records, no mention in any census returns. If she hadn’t been murdered by Jack the Ripper, with all the publicity surrounding him, if she had simply been strangled and dumped in the Thames, there would probably have been no record of her at all.

It’s that sort of unrecorded, undetected, unsuspected crime that fascinates me most. And others too. Jane Austen died a natural death in 1817… but her hair was later found to contain arsenic. Was she actually poisoned? Lindsay Ashford decides she was in THE MYSTERIOUS DEATH OF MISS AUSTEN.

Did Amy Robsart, wife of Elizabeth I’s favourite Robert Dudley, accidentally fall down stairs and break her neck or was she pushed. In KENILWORTH, Walter Scott decided it was murder.

In 1872, the skeleton of a woman was (allegedly) found, walled up, in Ightham Mote in Kent. Who was she? There have been plenty of theories, but nobody knows. There is no written record of the deed, no record of anyone missing. Anya Seaton based her novel GREEN DARKNESS on the story.

History, fortunately for the crime writer, is littered with doubts and questions, and that’s what inspires my writing. In my novel, SHADOWS, there is a murder that will, perhaps, never be solved, and there are echoes, or shadows, of murders from the past, that will remain forever unexplained… except that in my companion book, LONG SHADOWS, with three stories set in the 14th, 17th and 19th centuries, I do explain them. Because I’d really like to believe that some day, somehow, the truth will always out.

Check out PART I (punishment, science and law), and PART II (early law enforcement)

This will lead to a whole lot of extra research, Thorne. A wonderful post. I remeber seeing a docudrama on Inspector Jack Whicher.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Judith. I think I can remember a TV drama with Joss Ackland.

LikeLiked by 2 people